About

A MEANINGFUL LIFE

Abdul Aziz Said’s life was shaped by contradictions. A son of a prominent family raised in insecurity. A Christian from a largely Muslim world. An exotic Arab immigrant in conformist mid-century America. A scholar injecting humanity into the cold calculus of international relations. A deeply spiritual man in a secular field. And, above all, a child of conflict who dedicated his life to peace.

Reconciling these contradictions, reconciling conflict, and reconciling differences were the foundations of a groundbreaking career and a profoundly meaningful life.

Colonialism and Conflict: A Scholar’s Unlikely Path

On the Edge of a Wasteland

“For me removing boundaries was more important than defining boundaries. But when you remove boundaries, you must be careful that you are not going into a wasteland.”

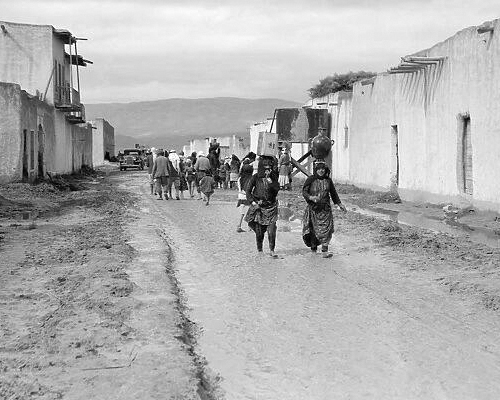

A typical village in northeastern Syria circa early 1930s. (The Granger Collection.)

Abdul Aziz Said Ishaq was born in Amuda, a small village of mud houses in French-ruled Syria in 1930. The village, located in the rural northeastern al-Jazira region near the Turkish border, had no electricity or running water. It had scorpions and sandstorms. The typical diet was limited to meat and rice, with fruit and vegetables a rarity. Diseases like dengue and typhoid fever and smallpox were pervasive. It was a world away from the life he would come to know as a preeminent professor in Washington, DC, but the experiences of his youth – conflict, displacement, discrimination, acceptance, religious and ethnic diversity, and political involvement – laid the foundation for the man he would become.

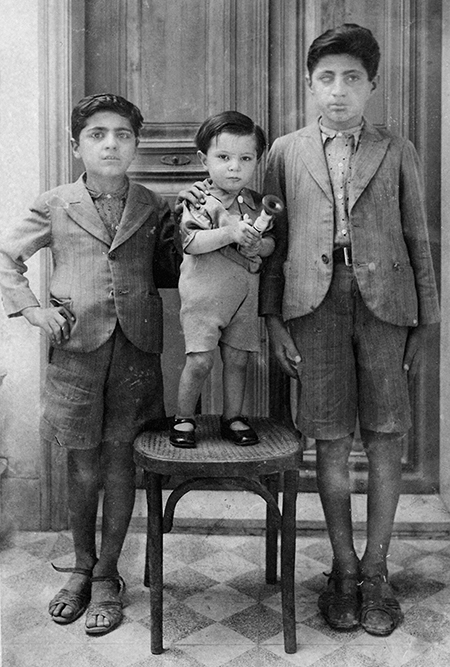

His father, Said Ishaq was a businessman, landowner, and political leader who initially rose to prominence during Syria’s French Mandate period in the early 1920s. A Syriac Orthodox Christian, he had escaped to Amuda at the age of 14 as a refugee from the violent attacks on Turkey’s Christian minority communities as the Ottoman Empire crumbled during World War I. His family was forced from their home in the majority Syriac Christian town of Qal’at Mar’a (now in Turkey). Ishaq’s father died just before the Armenian Genocide (known as the “Sayfo” to Christian Arabs), so Ishaq fled with only his mother and siblings, one of whom died along the forced march.

Fortunately for Said Ishaq, his family had a place of refuge. For five generations, the family maintained a small home and fabric store in Amuda. His father had traveled there regularly to trade fabrics. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Said Ishaq resumed this cross-border trading; owning the only fabric store in Amuda proved lucrative.

Using money earned in trading, Ishaq became a prominent landowner and a prosperous and influential member of the community. He made a point of establishing close ties with the area’s various ethnic groups, doing extensive business with Kurds (with whom he communicated fluently in Kurdish) and maintaining a strong relationship with the Shammar tribe (one of the largest and most influential Arab tribes).

Ishaq was a natural leader, well regarded by Muslims and Christians alike, and viewed as honest and generous. Reflecting his growing stature and reputation for integrity, he was elected mayor of Amuda in 1928. Although he would eventually become an ardent nationalist, Ishaq agreed to serve in the French Mandate’s Syrian Parliament after elections in late 1931.

French Legionnaires in northeastern Syria circa 1930. (Courtesy of French Legion Info.)

Destruction and Dreams

But the turbulence of the times caught up with Said Ishaq again. The French dissolved the Parliament in 1933, and their mandate sowed discord and violence – both pro- and anti-French – among various ethnic groups. As violence escalated, the French bombed Amuda in 1935. A year later a neighboring Kurdish tribe attacked the village and burned it to the ground, including the Ishaq’s home and shop. Said Ishaq’s family was rescued by members of the Shammar tribe who helped them flee on horseback. Abdul Aziz was just 6 years old. The family stayed in Damascus for about two years before the French authorities ultimately relocated them to Aleppo. During part of this period, Aziz’s father was imprisoned by the French for his nationalist activities. Ishaq was one of very few Christian leaders who sided with the nationalists. Aziz remembered the sting of hearing some local Christians refer disparagingly to his father as “Mohammed” Said – meant as an insult because most of the nationalists were Muslim.

With relocation to Aleppo, Aziz, and his older brother Fayek, experienced firsthand the cultural destructiveness of colonialism. They were forced to attend French schools as part of France’s policy of trying to turn the sons of nationalist leaders into Francophiles – its so-called “mission civiliatrice.” At school they were forced to abandon their traditional Arabic attire for French “culottes” – viewed as highly insulting in Arab culture. The brothers were harshly punished for speaking Arabic and learned to read and write in French long before they became literate in Arabic.

However, these cultural indignities paled in comparison to the violence inherent in colonial rule. In 1939, it was responsible for one of the most painful experiences of Abdul Aziz’s life. His three-year-old brother Riyad was struck and killed by a French military truck. Aziz carried his tiny brother’s bleeding, lifeless body home, and kept the memory of the taste of his brother’s blood for the rest of his life. Later that year, he endured the loss of his adored mother, Shemsa, a strong woman of mixed Arab-Armenian heritage. His father was in exile during this period. It was now up to his paternal grandmother to raise the six remaining children.

The British Army in the streets of Aleppo in 1941. (Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.)

In 1941, the violence of World War II came to Syria, with Vichy French troops fighting Allied forces. Aleppo was bombed daily as the French and British vied for control of the city. The young Aziz was forced to bear witness to the human and material destruction of the intense bombing. He had many memories of spending long hours in crowded, filthy bomb shelters, and a particularly vivid memory of a time when he opted instead to hide under a bed as glass and mud bricks shattered all around him. Food was scarce, and the family had to risk their lives to go out to find it. Aziz’s father returned briefly during this time but was re-arrested, leaving Aziz and his brother to “protect” the family during a terrifying period of non-stop fighting.

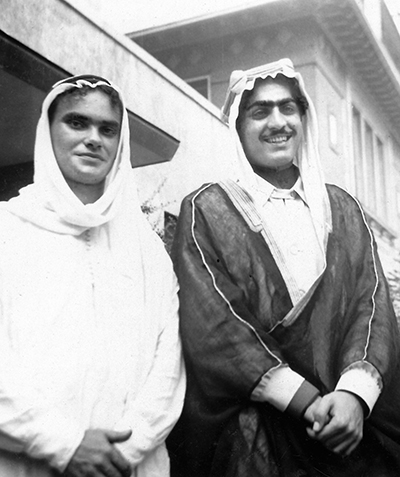

Aziz with a close friend in Aleppo in the late 1940s.

While much of Aziz’s childhood and teenage years were marred by painful experiences, they were tempered by some positive ones that helped shape his outlook on life. He fondly remembered returning from Aleppo to Amuda in summer, riding horses across fields and semi-deserts with his cousins, visiting villages at harvest time, and sleeping on the rooftop staring at a wide-open sky filled with stars and dreams of faraway places. Childhood in rural Syria also meant open horizons and no boundaries – nor any constraints on imagination.

Aziz also formed enduring friendships with members of the Shammar tribe, including his childhood best friend Khalil al-Hadi (whose father was the tribe’s leader in Syria and Iraq) and with people associated with the Sufi tradition of Islamic mysticism. The well-known local Sufi leader Sheikh Ahmad, his father’s close friend, had an especially important influence on Aziz. Said Ishaq relied on the Sheikh “to keep an eye on” his son during his absences from Amuda, and Aziz enjoyed sitting among the Sufis listening to their chants and drums. Aziz also became close to his Syriac Orthodox priest in Aleppo, once saving the little money he had for months to buy a radio for him.

His parents deeply instilled this generosity of spirit in Aziz. He often reminisced about how his mother sold her jewelry piece by piece so the children could afford shoes and other items, a memory that consistently brought tears to his eyes. He never saw his father turn away from someone in need. Aziz spoke often about how much he learned from his father – about the importance of leading by example, listening, being non-judgmental, a willingness to compromise, and treating everyone with dignity. He said that he never heard his father “utter a bad word about anybody.”

The end of World War II brought independence to Syria in 1946, and Said Ishaq won a seat in the new republic’s Parliament. Between 1946 and 1956, Syria was in a constant state of political upheaval and instability, with three military coups, 20 cabinets, and four constitutions during this decade alone. Despite the tumultuous environment, Aziz’s father remained in Parliament, even serving twice as deputy speaker. His long tenure in Parliament was especially exceptional – and a reflection of his character – given that he represented an area that was 80 percent Muslim.

Said Ishaq groomed his son to follow in his footsteps as a political leader. Aziz recalled the excitement of accompanying his father by car to Damascus and watching him in Parliament and official meetings. When in Amuda his father also encouraged him to sit in on political meetings.

However, while embracing his father’s values, it was the combination of the devastation of colonial rule and war, the tragic deaths of his younger brother and mother, the limited contact with his father, dislocation, and the many instances of violence Abdul Aziz witnessed that most profoundly shaped much of his worldview forever. He was left with a revulsion to war, a passion for peace, and a deep-seated appreciation for the value of nonviolence.

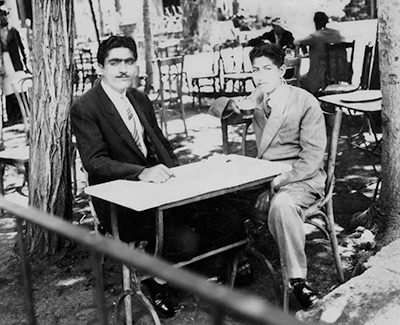

Aziz relaxing during his time as a student in Beirut in 1948.

New Worlds, a “New” Name, and New Perspectives

By 1947, with the encouragement of his father and older sister, Aziz left to study at American University of Beirut’s International College. Beirut opened a new world for him with foreign friends, education in English, and cafes on grand boulevards. After completing the required two years at the International College, Aziz enrolled at The American University of Cairo (AUC). He was excited about AUC, but his expectations were soon dashed as he witnessed – and was also a target of – prejudice by Muslims against Coptic Christians. Disappointed Aziz left the university after less than a year.

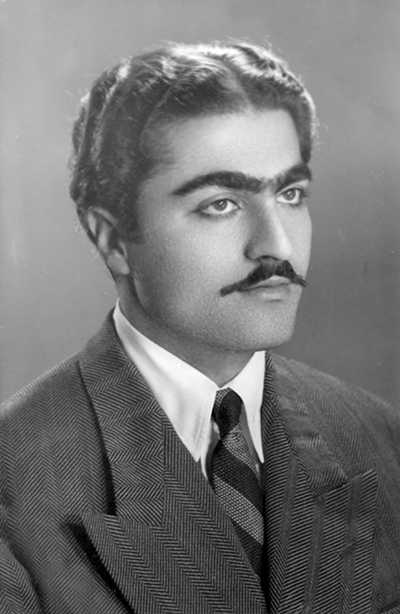

His experience in Cairo influenced how he chose to identify himself going forward. He began using the prefix “Abdul” (rarely used by family and friends) and adopted his father’s first name, Said, as his last (an old Arab custom used mainly by tribal Arabs). “Aziz Ishaq” was readily identifiable as a Christian; “Abdul Aziz Said” would most commonly be viewed as a Muslim name. Aziz said the reason was to ensure he wouldn’t be judged – or possibly excluded – simply by virtue of his name and Christian identity. After Egypt, Aziz traveled for a few months and explored studying in Europe but ultimately decided to pursue his education in the US.

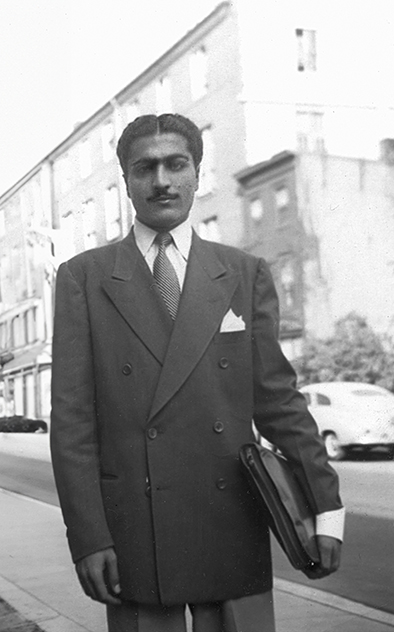

In 1950, Aziz arrived in New York and found the modern, vibrant city intoxicating. He was especially impressed by the dynamism and spirit of enterprise. Years later, he would describe his surprise upon his arrival, seeing a vendor selling watermelon in pre-cut slices. He was fixated, having never seen it sold this way. Taking notice, the vendor exclaimed “If you don’t like watermelon in slices then I’ll sell it to you by the pound.” To Aziz, this seemingly innocuous encounter symbolized something far greater: American innovation as well as pragmatism. A few weeks later, he arrived in Washington, DC where a friend of his father’s had offered lodging. After taking many courses at two other local universities, Aziz finally enrolled fulltime at American University (AU) in 1953.

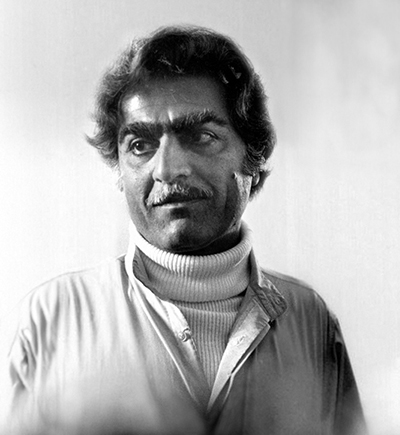

America also offered other novel opportunities. An Arab-American acquaintance with Hollywood connections was convinced that with his good looks and charisma, Aziz could easily become a movie star (in a humorous coincidence Aziz was often mistaken for Omar Sharif for most of his adult life). Although flattered, he declined the offer. However, he did not decline the opportunity to date and socialize with women, both new experiences.

Aziz (third from left) with his circle of Arab college friends in Washington, DC in the early 1950s.

American Life: Segregation, Studies, and Soup

While many aspects of American culture were exciting, some were not. In the early 1950s, Washington, DC was a completely segregated city. More than once, Aziz and his close circle of Arab friends were turned away from cafes or theaters because one of the group was of mixed race. He also recalled the father of an American friend being pulled aside by the manager of an exclusive country club inquiring if Aziz was Jewish because Jews were not permitted. Aziz was also aware of his own minority status in the largely white, Protestant university where he would make his home.

Being a foreign student came with some difficulties. Since his education had been in the French language and under the French system, Aziz found studying in English and aspects of America’s educational system challenging. He overcame this by putting exceptional effort into his studies, often falling asleep in the Library of Congress after hours of intense work.

In addition to pressure to succeed academically, for the first time Aziz had to worry about money. His father – who supported him in Beirut and Cairo – had remarried and started a second family, so resources were limited. Aziz often mentioned how he and his friends “economized,” discovering they could make tomato juice and soup from ketchup and eat free crackers in the school cafeteria. He found various jobs to support himself while he worked toward his PhD, including applying soup can labels, teaching horseback riding, and working as a researcher for a prominent diplomat. In what little free time he had, he enjoyed relaxing with other Arab students, eating at cheap Arab restaurants, playing cards, or drinking coffee in cafes.

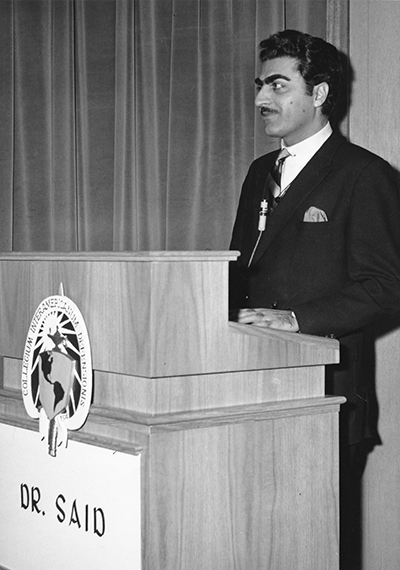

Abdul Aziz on his first day as an Adjunct Faculty member in 1957.

The Birth of an Academic Star

By the time Abdul Aziz received his undergraduate degree at American University in 1954, it was increasingly clear that he would be unable to return to Syria, start a political career, and follow in his father’s footsteps. Syria’s political instability was getting even worse, and the country was moving towards authoritarianism. With regret, his father acknowledged Aziz would be unable to return and enter Syrian politics as had always been the plan. Realizing he had a keen interest and aptitude for academics and encouraged to pursue further study by both his father and AU professors, Aziz opted to pursue master’s and then doctoral degrees in International Relations. He was a brilliant student, receiving the highest marks and distinction for both degrees.

Youngest Professor, Greatest Mentor

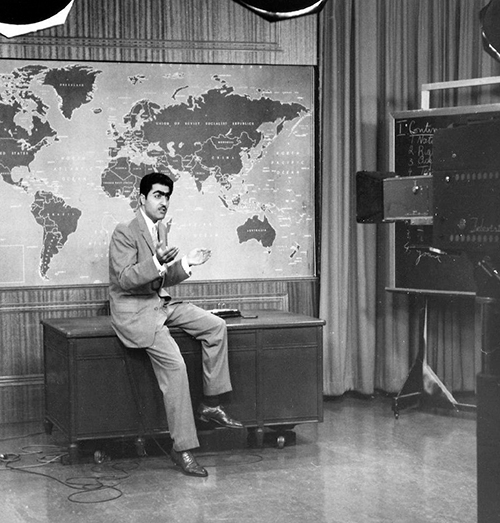

Aziz taught his first course as an Adjunct Faculty member in 1957. By 1958, he was the youngest Assistant Professor at American University’s new School of International Service (SIS). Abdul Aziz’s rapid rise through the professorial ranks was unprecedented, with promotions to Associate Professor in 1960 and Full Professor in 1964.

Even as a young professor, Said demonstrated not only a powerful intellect, but an interactive and compelling teaching style that stood apart from the rest. His talents did not go unnoticed and in 1959, he was chosen to teach a weekly course on world politics on a local television station. The program, “Classroom 9,” received rave reviews and eventually earned Said a Sylvania Award. At the time, many saw the selection of “Abdul Said” – a brown, younger man, with a strange accent – for a program viewed largely by white Americans as further evidence of his exceptional charisma and skills as a teacher.

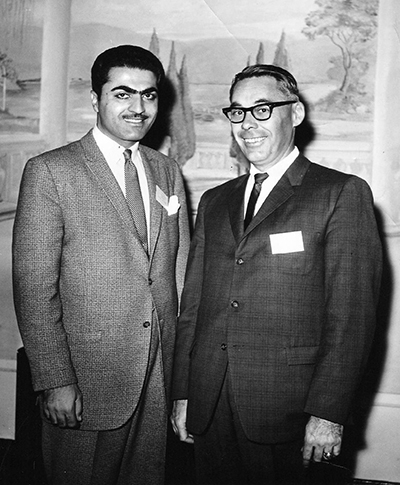

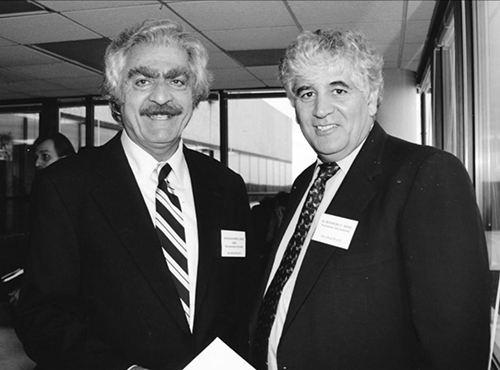

In 1960, Abdul Aziz met Dr. Charles O. Lerche, Jr. (Charlie) who was to become his mentor, academic collaborator, and best friend. In addition to their intense professional relationship, the pair also enjoyed each other’s company outside of AU, socializing and going to restaurants and night clubs.

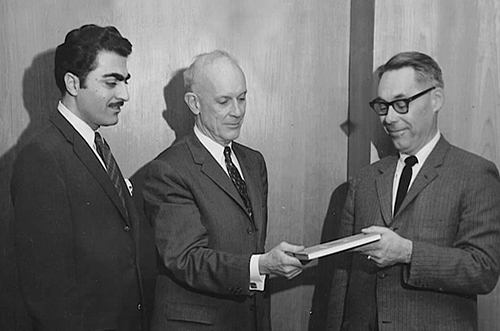

Abdul Aziz with his mentor and best friend Professor Charles O. Lerche, Jr. in Washington, DC in 1960.

Said and Lerche shared an office: Room 206. Aziz would occupy this same office – which became legendary as a buzzing center of student and visitor activity – for 50 years with a very large photograph of Charlie Lerche dominating one wall. Throughout his lifetime, Aziz often spoke of the extraordinary impact Charlie had on him. He credited Professor (later Dean) Lerche with teaching him discipline and how to write, enhancing his analytic and critical thinking abilities, and encouraging him to challenge existing theories with rigorous research and “outside-the-box” thinking. Possibly the most essential thing Abdul Aziz learned was the importance of academic collaboration. He took this lesson to heart, collaborating with colleagues and students on myriad projects for six decades.

Concepts of International Politics

While Abdul Aziz and Charlie Lerche cooperated on many academic endeavors, their greatest achievement was writing Concepts of International Politics (first published in 1963), a textbook on international relations that filled a glaring gap in existing texts. At the time, the study of international relations theory was dominated by “Power Politics” and the concept of “Realpolitik.” It was Lerche’s and Said’s goal to produce a text that introduced new concepts such as ethics and values. They also wanted to challenge the accepted Western interpretation of global affairs, and its failure to address issues relevant to non-industrialized countries.

Professor Said with AU’s School of International Service Dean Ernest S. Griffith and Professor Lerche with the first print copy of Concepts of International Politics in 1963. (Photo courtesy of American University.)

They succeeded in producing a controversial, yet groundbreaking, treatise suggesting a new paradigm for viewing international relations theory that analyzed largely unaddressed issues, including the role of values and ethics, the politics of development and rising expectations, the impact of mass media and technology, and the exploration of the various nonviolent means for conflict reduction. In one of the first reviews, Professor Maurice Waters noted the unique approach of the authors, calling the book “a highly credible undertaking and the frankest attempt yet … to break out of the traditional mode [of power politics].”

Sadly, only three years after publishing their first book, Dr. Lerche passed away from cancer at the age of just 48. During Charlie’s last weeks, Aziz made a point of spending as much time as he could with his dying colleague and best friend. While Aziz was in shock and grieved deeply, throughout his career, he carried forward many of the ideas and ideals that they shared, including mentoring Charles O. Lerche III – Charlie’s son. In a fitting tribute, the Fourth (and final) Edition of the textbook – now titled Concepts of International Politics in a Global Perspective – lists Dr. Charles O. Lerche III as a third author for his work with Abdul Aziz Said on updating and expanding the book.

Trailblazer, Iconoclast, Author

Thought Leader: New Actors

Said’s groundbreaking collaboration with Charlie Lerche was only the beginning of a long career as a pioneer and thought leader, challenging conventional theories, shining light on overlooked variables, and always putting human dignity first. Although he was an exceptional theoretician, he had limited patience for ongoing methodological and theoretical arguments based on the positivist interpretation of world affairs. He believed in a more nuanced, normative approach to scholarship that factored in ethics and values.

Said stressed the limitations of treating political science the same as the physical sciences. He believed the emphasis on “objective,” abstract thinking distracted from the real issues like poverty, ethnic strife, and underdevelopment. According to Said, the cause of scientific truth is no more advanced than that of human freedom if “frontier thinking” implies a suspension of moral judgements of the objects of inquiry.

His trailblazing views – along with a compelling teaching style and charisma – made him one of the most popular professors on campus and his courses almost always had waitlists even though they were often very demanding. His new perspectives on international relations also led Said to become a prolific writer. During his career, he authored or co-authored over 400 papers and over 20 books. Reflecting his incredible energy and commitment, he didn’t slow down over time. In fact, his academic output was at its highest during the last years of his career.

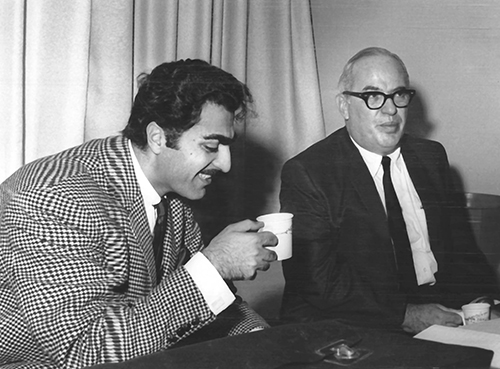

Abdul Aziz with one of his former mentors and thesis advisors Professor Samuel L. Sharp at American University in the early 1960s. (Photo courtesy of American University.)

During the 1960s, Said continued to introduce concepts and topics often unaddressed by scholars of international relations, such as colonialism and the decolonization process, the role of the global illicit drug trade, and the impact of multinational corporations. Novel at the time, his analysis opened new avenues for research now viewed as mainstream. He also wrote about the Cold War and, with the proliferation of nuclear weapons, urged a re-evaluation of the concept of global “security.”

He continued pushing intellectual boundaries during the next decade. His 1971 Revolutionism was prophetic in predicting increased authoritarianism, greater international fragmentation, and alienation within many societies leading ultimately to insurrection. In the aptly titled Protagonists of Change, Said sought to explore the interactive role between development and “subcultures” within societies. He also identified ethnicity (and ethnic conflict) as well as religion as significant issues affecting international affairs. Later in the 1970s, Said focused more on issues related to human rights and social justice, broadening the concept to include preservation of individual human dignity, and advocating inclusion of human rights as a key component of US foreign policy and a focus of international organizations.

Although he never intended to be a Middle East expert, Said’s background made it inevitable that he was frequently asked to advise and comment on developments in the region. He also wrote on regional topics of particular interest to him, including strategies for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, pathways to democracy in the Islamic world, and analysis of the political situation in Syria.

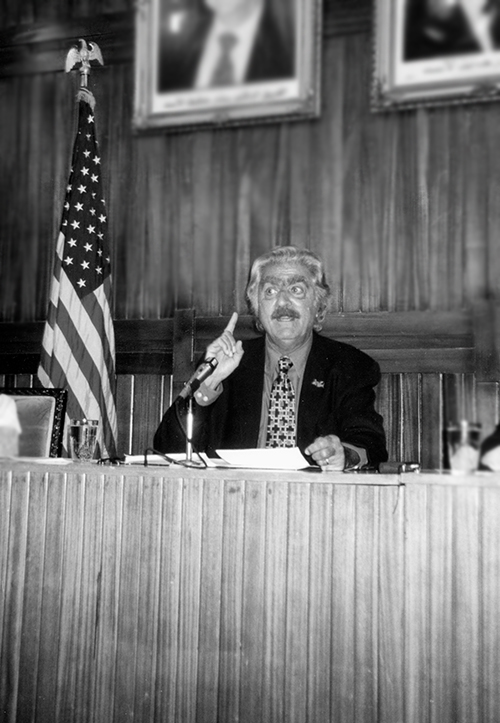

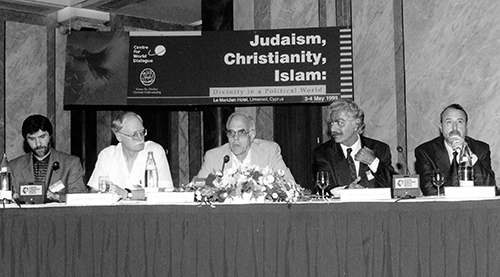

Professor Said serves on a panel at a conference sponsored by the Centre of World Dialogue in Cyprus in 1999.

Visions of A Peaceful New World Order

By the 1980s and 1990s, Professor Said increasingly concentrated on issues related to cooperative global politics and the concept of a new world order based on improving the universal human condition. During this period, he also began to write and work in peace studies and nonviolent conflict resolution. Said ultimately became a giant in the field, publishing extensively and actively engaging in resolving conflicts globally. By the mid-1990s, he succeeded in establishing the International Peace and Conflict Resolution (IPCR) Program at the School of International Service. Recruiting leading academics in the (then) nascent field, this program became one of AU’s most popular degree offerings and was ranked as one the world’s top IPCR graduate programs. In 1996, Said also became the first occupant of AU’s Mohamad Said Farsi Chair in Islamic Peace. The position enabled him to explore in depth the concept of peace in Islam during a critical decade for the Muslim world.

Professor Said continued to focus his work almost exclusively on peace and nonviolence and by the 2000s had introduced the twin concepts of “spiritual and personal transformation” as critical to becoming an effective practitioner and teacher of nonviolence. Given his direct experience, Said’s passion for world peace and deep compassion for victims of violence were a fitting focus for the remaining years of his career. At his core, Said wanted to do whatever he could to protect future generations from the pain and suffering of the violence he endured during his youth.

Activist, Innovator, Leader

While Said was changing approaches to the study of international relations and helping create the field of peace studies, he was also having a profound impact on the university he loved – AU’s direction, its programs, its culture, and its faculty and students. He never stopped investing considerable time and effort in developing numerous proposals for how to improve the university and the educational experience it offered. Many of his proposals were visionary, and rooted in his views of the unique academic and social roles the university could – and should – play.

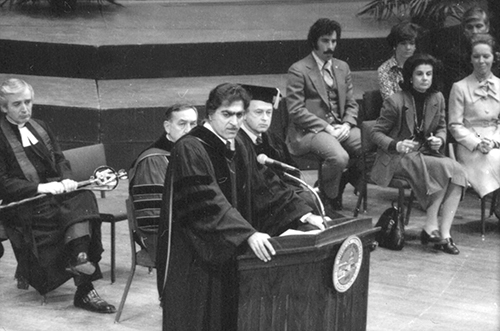

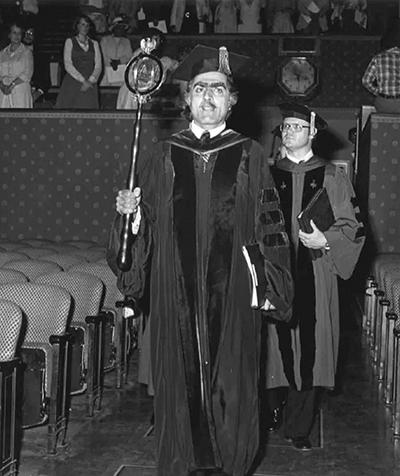

Professor Said carrying the ceremonial mace in the 1978 graduation procession. Traditionally the mace is carried by an academic with the highest rank by honor and standing. (Photo courtesy of American University.)

Academic Reform and Leadership

He consistently urged AU to take advantage of its location and orientation to fill what he saw as a vacuum in Washington as a major public policy institution. He proposed creating centers and institutes that would advance that goal, including an equal opportunity institute, a global communications network, a global information data center (well before “data collection” became the norm), a global public affairs network, and a national leadership institute.

He wrote about the need for true academic reform and advocated strongly for cross fertilization among disciplines, arguing that the university needed to become “a universal storm-center of innovation.” He challenged the traditional narrow hierarchy within individual schools and the university as a whole, arguing for greater representation and input from faculty and students. He also pushed the university to recognize its social role, proposing ways to dismantle “the fiction of scholarly distance” from society and the reevaluation of the degree system that he saw as inherently biased against the underprivileged.

Although he was not interested in administration, Abdul Aziz saw it as part of his duty to participate in the university’s governance. He served in the university Senate for many years, including as its Chair. Despite his demanding schedule, he willingly sat on numerous AU committees ranging from chair of the committee on academic development, to president of SIS faculty, to member of search committees for provosts and presidents.

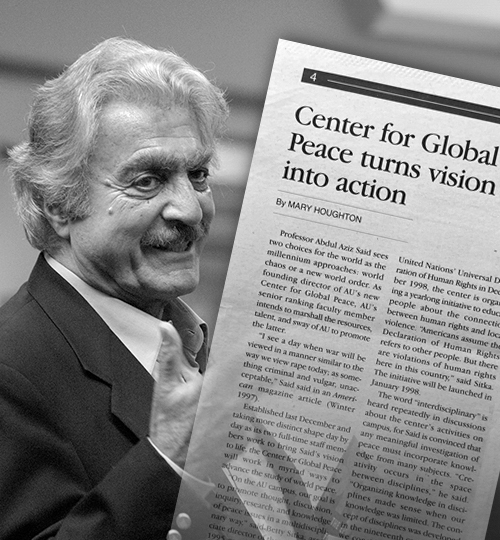

While Professor Said was continuously identifying ways for the university to advance, he was also busy establishing and running his own centers and institutes. He founded and directed 15 centers and institutes during his career. One of the most important was the Center for Global Peace (CGP), which hosted important international conferences and provided a forum and facilitation for several countries and ethnic groups to gather to resolve disputes. In addition to his own centers, Professor Said secured 3 endowed chairs for the university – in Islamic Studies, Kurdish Studies, and Islamic Peace. In 2023 American University established the “Abdul Aziz Said Chair in International Peace and Conflict Resolution.”

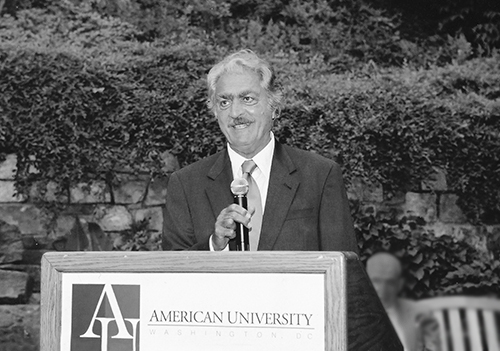

Dr. Said was given the honor to be the keynote speaker at AU’s groundbreaking ceremony for its new School of International Service in 2007.

Because of his superb communication skills, his well-known calm and compassion, and (later) his seniority, the university often turned to Abdul Aziz for leadership during times of crisis. Sometimes these crises were internal – the destabilizing resignation of two AU presidents, for instance, or the occasional disputes between faculty and administrative leadership.

At other times, he was sought out to calm anxiety and fear from external events – offering comfort after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, providing a “safe harbor” for Jewish and Arab students during the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, and hosting informal forums for students on opposite sides of the revolutions in Iran, Chile, and Nicaragua. Immediately after the 9/11 attacks, he was asked to hold a university-wide discussion session during an unprecedented time in the students’ lives and simultaneously provide reassurance to Muslim students. In October 2001 he was also asked to speak at the Interfaith Prayer at the Washington National Cathedral.

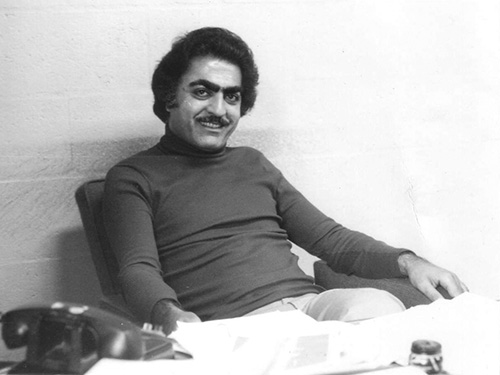

Professor Said in the early 1970s reflecting the more “laid back” era.

Rebel Rebel: A Voice for the Underdog

Always an advocate for the underdog, Said was an activist on and off campus from his earliest days at AU. As a first-year student, he agreed to hide a professor’s papers to ensure they would not be confiscated during the McCarthyism hysteria. (Notably AU was one of the few universities that resisted McCarthyism at the time.)

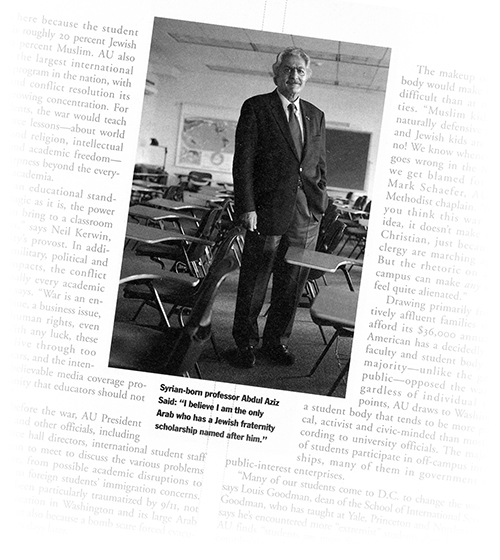

Reflecting his own minority status, Said often became a voice for minorities at AU. In the late 1950s, as the school’s youngest Assistant Professor, Abdul Aziz put his career on the line to help a group of Jewish students who wanted to participate in Greek life at a time when all fraternities at AU had sectarian clauses that prevented Jews (and other minorities) from joining. Said raised the issue with the administration and asked for the removal of sectarian clauses. The answer was a resounding no.

Unwilling to accept defeat, Said asked the university Senate to allow establishment of a chapter of the Jewish fraternity Phi Epsilon Pi (now Zeta Beta Tau) on campus. He enjoyed telling the story that after he made his motion, it was seconded by a tiny, elderly professor who chastised the Senate saying, “So, it takes a young Arab and an old Jew to make a Jewish Fraternity possible!” The motion was approved and Professor Said became the faculty advisor to Phi Epsilon Pi – which eventually welcomed members from other minorities – for over a decade. His commitment was rewarded in kind when the “Phi Eps” established a scholarship in Professor Said’s honor. The fraternity also bestowed him with The Phi Epsilon Pi “Living Legend” award, one he cherished above all others.

Said’s activism included deep engagement in the civil rights movement on and off campus. He encouraged his students to participate in Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 March on Washington and wrote memos to AU presidents outlining his concerns about the significant underrepresentation of minorities – especially Black Americans – at AU and proposed strategies to create a more diverse student body. For example, in 1971 he proposed that AU offer 100 scholarships to Black students in need of financial aid. He practiced what he preached, with one former assistant observing that his teaching assistants were always a diverse mix of race, gender, religion, and ethnicity.

His concerns extended beyond the university to the community at a tumultuous time when Washington, DC was convulsing with racial tension and riots. During the early 1970s, Aziz worked with esteemed local leaders such as Walter Washington and Julian Dugas who were grappling with these issues as well as the desire for “home rule” for the District.

During the Vietnam War Abdul Aziz held frequent informal “sit in” discussions with students, encouraged them to demonstrate against the war, and marched alongside them. He remembered getting calls at all hours to bail out students arrested at anti-war rallies.

Redefining and Advocating for the AU “Family”

His advocacy at AU extended beyond the students. More than once, Said initiated efforts to increase the pay for campus custodians, cafeteria workers, and other employees. He encouraged students to participate in demanding fairer pay standards and was usually successful. His commitment to treating all workers at AU as full members of the university “family” was genuine and deeply held. He dedicated one of his books to an SIS janitor, and when he realized the janitor could not read the dedication because he was illiterate, Aziz enlisted students to tutor adult reading.

Said was modest about his impact on AU and his advocacy for justice, but he did not disagree when he was asked late in life if he would characterize himself as an activist (or troublemaker) in addition to a scholar.

Professor Said in class in 2005.

A Teacher at Heart

One of the reasons for Said’s deep connection to his university was his love for his students and fellow professors. Throughout his career of writing prolifically, travelling extensively, advising leaders and policymakers around the world, and so much more, he remained a teacher at heart. He always gave priority to teaching and consistently turned down offers to take leadership roles in AU’s administration, at one point even declining an opportunity to serve as dean and later university president.

Thanks to his seniority and the high regard and affection his colleagues had for him, however, as noted he did serve as an informal and formal academic leader. For years he directed the International Peace and Conflict Resolution (IPCR) program he founded. When he did take on leadership roles, he approached them in the same way he approached teaching and his life, with an openness to ideas, respect for individuals, and an emphasis on dialogue and consensus rather than top-down direction.

One of the professors in the IPCR program remembered Said’s management style as “unconditional positive regard,” a warm and supportive approach that gave those working under him considerable responsibility and flexibility.

On sunny days Professor Said often met with students in his “outdoor office” and favorite bench outside of the School of International Service.

Students First

Said was committed to his colleagues, his university, and his scholarship, but his students always came first. He loved to teach and hated to miss class, even when he was called away for meetings with the US State Department or by other US government officials. He was vigilant about keeping his office hours – something many college graduates know is not always the norm. And, when he could not be found in Room 206, he would be in his “outdoor” office, sitting in the sun on a bench in front of SIS meeting with students. He was an exceptional educator, receiving an unprecedented number of university faculty teaching awards.

He loved opening young minds and exposing them to new ideas and perspectives, which may be why he said the course he enjoyed teaching the most was for freshmen: “Introduction to World Politics.” He disdained the traditional teacher-pupil paradigm, declaring that every person in a classroom is both a resource and source of knowledge for others. He said that the student-teacher relationship is at its best when the roles of teacher and student are repeatedly reversed and encouraged students to regard learning as a lifelong journey. He wanted to teach students how to think, not what to think.

In keeping with his philosophy, Said adopted a more casual give and take style of teaching, sometimes holding classes outside sitting in a circle or in his library at home. When he began a class, he asked each student to introduce themselves and provide background. He also encouraged each student to meet with him individually. Said saw connecting at the individual level as a duty. He also believed in experiential learning through volunteering or activism in the community, applying academic skills to make the real world better. For example, Said developed a program called Project PEN that had IPCR students teach nonviolent conflict resolution skills in local public schools.

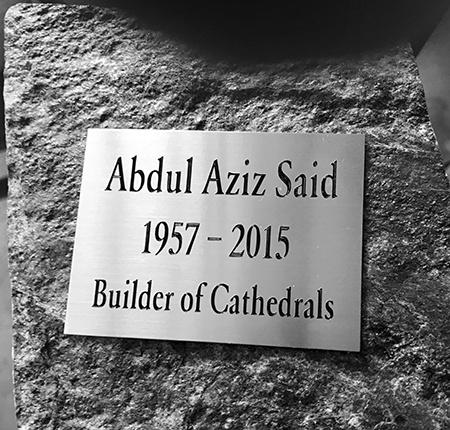

Building Cathedrals

Said was revered by the many teaching assistants (TA) who worked with him throughout the years, many of whom stayed in touch throughout his lifetime. One former TA, a professor, said that while he effectively guided her thesis research, “by far the most important gift he gave me was witnessing how he taught.” “Professor started each new class saying, ‘in this class, learning is not a one-way path, it’s not a two-way path but a space for multiple paths where all students could bring their ‘full selves’ and be seen and heard regardless of viewpoints. I try to model Professor when I teach and remember the most profound and transformative gift, I can give students is to truly honor them.” When asked to describe Said in just a few words, another former TA, a senior US State Department official, said, “Life changing teacher and mentor, activist and troublemaker, bridge builder, a rare soul who lived the talk.”

Said was just as committed outside of the classroom, mentoring and counseling countless students. He opened his office doors, sharing his time generously and offering each visitor, one student remembered, “deep respect, a warm smile, sage insights, and a cup of tea.” He would celebrate his students’ milestones and accomplishments with them. When a student came to him with an academic or personal problem, he would often close his eyes as he listened, giving his full attention before speaking himself to offer advice or consolation.

On many occasions, he even provided financial help to disadvantaged students so they could buy books, pay rent, or even get a decent meal. Often the money came from his own limited teaching salary, but when the need was beyond his means, he had no qualms about going to well-off friends for help.

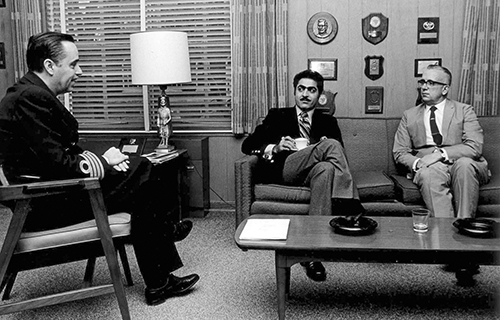

Professor Said meets with a senior naval officer and other staff before giving a lecture at the US Naval Academy in the late 1960s. Said was invited to lecture at every US military academy throughout his career. (Photo courtesy of the US Navy.)

Said did not limit his teaching to American University. Starting during the 1960s he made time to lecture at every US military academy. He believed it was important because his perspectives on conflict and peace were uncommon at these academies. Said was also a sought-after educator at the US Foreign Service Institute, and lectured at public schools, places of worship, and retirement homes as well.

Said’s impact on those he taught, and their lives, was profound. As one student noted, “Anyone who sat with Professor felt that sense of being deeply seen, heard, and honored to the core. What I learned from witnessing him in the classroom – the passion and commitment he brought to his students year after year, and the way he’d treat everyone with such dignity and respect, recognizing their full humanity – was the greatest education I received.”

One of Said’s favorite ways to make a point was through parables. Some of these “Saidisms” were ancient, remembered from his childhood and translated from Arabic. Others he made up himself. Still others were in the Western tradition. One that he used frequently illustrates his approach to teaching, his students, and his scholarship:

Upon retiring in 2015, Professor Said was given this gift by the Peace Studies Department that he founded. It is an actual piece of stone from the original School of International Service building where he began his career six decades earlier.

A man was passing by a quarry one day and noticed three men hard at work. When he asked them what they were doing, the first said, “I am working to support my family.” The second said, “I am cutting stone.” But the third lifted his eyes to the sky and said, “I am building a cathedral!”

Professor Said never forgot that with every lecture and every interaction with a student, he was building a cathedral.

Scholar-Diplomat, Advisor, Peacemaker

Abdul Aziz Said was not only a scholar and professor of international relations and conflict resolution – he was also an active practitioner. He took the “service” in School of International Service seriously, and strongly believed that all faculty had a responsibility to work in international service.

An Act of Congress and Public Diplomacy

For decades he actively participated in US educational and cultural public diplomacy efforts, held meetings with senior foreign government officials, held lectures for US diplomats and military officials, worked directly on specific projects for the US government, including the White House, and engaged in conflict resolution efforts in several regions under the auspices of non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

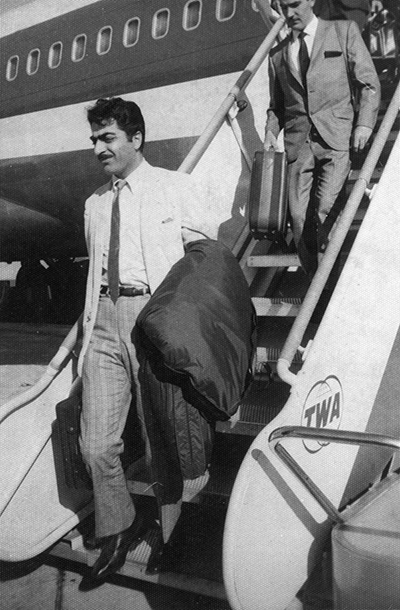

Professor Said disembarking en route to the Middle East for a lecture series on behalf of the US State Department in the early 1960s.

Said’s “official” travels began in 1961 when, with funding from a Rockefeller Foundation grant, he visited Tunisia and later Lebanon. His trip and meetings with Tunisia’s President Bourguiba and other senior officials led to articles on the political climate in Tunisia, a report on Tunisian foreign policy, and briefings for US State and Defense department officials on Tunisia and Middle Eastern perceptions of the US. (Interestingly, since Abdul Aziz was not yet a US citizen at the time and it was important that he travel as an American, he received his citizenship through an act of Congress.)

Professor Ambassador

By the early 1960s, Said was becoming known at the State Department and, through his lecturing at military academies, at the Defense Department as well. In 1964, the State Department, under what was then called the Bureau of Education and Cultural Affairs (BECA), sent him on a successful lecture tour in five Arab and three African countries, focusing mainly on the US political system and foreign policy in the Middle East and Africa. Said was an ideal speaker for the US government not only because he was of Arab origin and could lecture in both Arabic and French, but also because he represented the “successful immigrant” story – the embodiment of the American Dream.

Professor Said with the Oba of Benin and US diplomats on his first tour for the US Department of State in 1964. (Photo courtesy of US State Department.)

Said continued to travel annually for the State Department over the next three decades through its various iterations of public and cultural diplomacy: BECA, the United States Information Service (USIS), and the United States Information Agency (USIA). In addition to the Middle East and Africa, he lectured in Europe and Central and South America. However, he became especially well known in the Middle East, where ambassadors and cultural affairs officers often specifically asked for him. Cables and letters about his lecture tours underscore the positive impact they had on local impressions of the US.

While on these trips, he also gave hundreds of press interviews, met with local government officials, and was often consulted by US ambassadors and other embassy staff on his assessment of the political situations in the various countries. American ambassadors regularly used Said as a go between in countries where he had access to the highest echelons of government.

Storm Warnings

Professor Said maintained lifelong relationships with many US ambassadors and attaches, who called on him as they advanced in their careers for informal and official advice, especially during periods of crisis. One of his teaching assistants, Keith Rosenberg, remembered Said being summoned to the White House on October 5, 1973. Rosenberg observed that Said was uncharacteristically quiet when he returned and “the next day the Arab-Israeli War started.”

As a result of his extensive travel in the Middle East in the 1970s, Said was keenly aware of developing dissent against governments in several countries and deep frustration about the lack of progress on the Israeli-Palestinian issue. Said also spent time in Iran meeting with government officials, the opposition to the Shah, and imprisoned victims of torture. He warned that if festering problems were left unaddressed, the result would be civil unrest, more animosity towards the US (and the West in general), and terrorism.

In the wake of the Iranian Revolution and the ensuing hostage crisis and other turmoil that followed, Dr. Said was asked to serve on President Carter’s Committee on the Islamic World in 1980. The Committee’s mandate was to identify strategies to strengthen US relations with Muslim countries and develop a plan to “improve the US public’s understanding of the Islamic World.” Although the Committee was active for just a year, it developed several concrete proposals as the Middle East entered what turned out to be among its most tumultuous decades.

The 1980s began with the Iran-Iraq War, were marked by an almost unbroken string of upheavals and conflicts – including the assassination of Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon followed by the US’s disastrous foray into the country, and the founding of Al Qaeda, to name just a few – and were capped in 1990 with Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

Said was highly critical of US and Western Middle East policies. He was at odds with the Reagan administration’s approach to the region, and made his views known to the US government largely through unofficial channels and through the media, writing strong editorials in national newspapers and giving television interviews. He argued that policymakers lacked in-depth understanding about the underlying factors driving war, ethnic conflict, and terrorism as well as the beginning of what would come to be known as “Islamic fundamentalism.”

Abdul Aziz with peace activist and academic Dr. Mubarak Awad in the mid-2000s. The two men worked closely together on numerous conflict resolution projects and the Arab-Israeli peace negotiations.

While not officially consulted by the Reagan administration, Abdul Aziz was quite active working on possible solutions to the Arab-Israeli problem. In 1985, he met Mubarak Awad, known at the “Palestinian Gandhi,” who started the first nonviolent Intifada (resistance) in occupied Palestine in 1987. Said and Awad worked closely together, traveling to meet with Palestinian officials, including Yasser Arafat, as well as peace-oriented Israeli officials and academics. Through their work they helped build trust between Palestinians and Israelis and lay the groundwork for Yasser Arafat’s recognition of Israel in 1993.

During the 1990s, with the establishment of his Center for Global Peace (CGP), Said embarked on several “Track Two Diplomacy” initiatives. As a forum for programs and initiatives to enhance the study of world peace and analyze the factors behind violence and upheaval between countries and ethnic groups, the Center held numerous conferences and workshops related to a wide range of conflicts, including those between Palestinians and Israelis, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Ireland and Northern Ireland, Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan, and opposition groups in Syria. The CGP also held several major conferences on Islam to improve understanding between Muslim and non-Muslim countries and identify the issues driving Islamic fundamentalist movements. Said’s work in this area led to a request by the US National Security Council during the Clinton administration to be briefed on Islamic fundamentalism. During the 1990s Said was also involved in trying to improve deteriorating relations between Syria and the US, acting as a go between with Syrian President Hafez Al-Assad, and he also worked with the State Department on preparation for the Oslo Accords between Israel and the PLO.

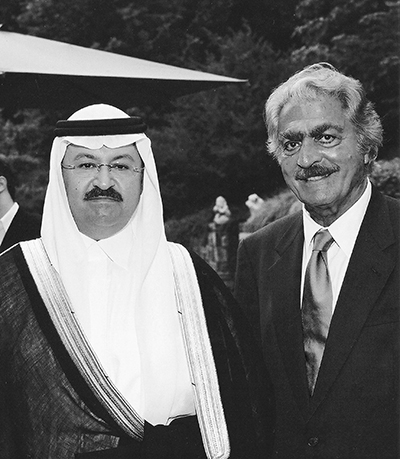

Professor Said with Shammer tribe member Sheikh Ghazi Al-Yawar, Iraq’s interim president, in 2004. In addition to his negotiation skills and regional knowledge, Said’s long-standing ties to the Shammar tribe were instrumental to his work on the “Future of Iraq Project” and the establishment of Iraq’s Governing Council. (Photo courtesy of American University.)

In 2002 Professor Said was asked to join the Democratic Principles Working Group, part of the “Future of Iraq Project” established by the State Department under President George W. Bush’s administration. He made significant contributions to this effort, including preparation of a report on “Transition to Democracy in Iraq.” (In an interesting twist of fate, Said was instrumental in convincing the US to accept Ghazi Al-Yawar as Iraq’s first President. Al-Yawar was the nephew of Said’s close college friend, Sheikh Mohsen Al-Yawar, head of the Shammar tribe that had rescued Said’s family from its burning village so many decades earlier.) With his work on Islam and peace becoming well known, the Bush administration also consulted Said on how to improve the US image in the Islamic world in the post-9/11 era of growing discontent and radicalization in several Arab and Muslim countries.

Towards the end of the 2000s and into the early part of the next decade, Professor Said served as a sounding board and as an official advisor to the US government on the (first) Arab Spring as well as the civil war in Syria. He wrote and spoke about both issues, and the CGP held related meetings and workshops. Said’s wife recalled that during this period, it seemed like the Syrian Desk at the State Department had her husband’s cell phone on speed dial.

In addition to providing opinions and advice he also was officially engaged by the US government. He served as Co-Chair of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research’s “Negotiated Solutions for the Crisis in Syria Group” for the UN-sponsored Geneva II Conference on Syria. Said also advised the Acting Assistant Secretary of State under the Obama administration on the Syrian political situation. The Syrian civil war took a personal and emotional toll on Abdul Aziz, bringing back memories of his own experiences as a child. He even privately wondered whether he should have returned to Syria in the 1950s and could have made a difference, but recognized the reality that under such an authoritarian regime this would never have been possible.

Said’s success as a “scholar diplomat,” like his success as a “scholar activist,” rested on the fact that he saw no distinction between the two roles. In fact, they were interdependent. The way he saw and taught about the world as a professor was not just theoretical – it also drove the way he approached informal and formal diplomacy. As a cable from a US embassy noted after a visit from Abdul Aziz, “Dr. Said’s success was to a large extent due to his integrity as a scholar.”

Meaning, Sufism, Transformative Thinking

“Once we change our conscious beliefs — the unconscious ideas and abstractions that hold our world in place — our inner experience and outer engagement are transformed.”

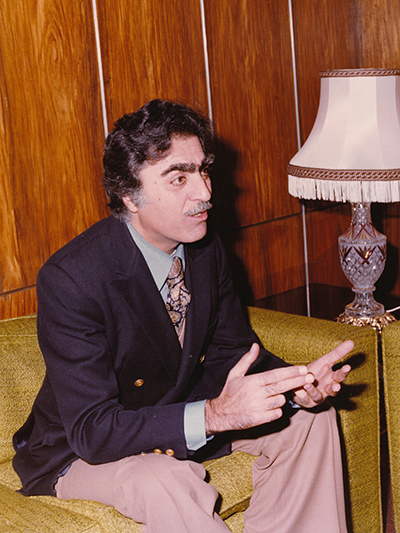

Prior to his search for greater meaning Said was very concerned with his outer appearance – stylish clothes were a must.

Having it All: Not Having Enough

By any measure, Abdul Aziz Said’s career was a dazzling success, and that success came early. At only 40, he had more academic accomplishments, successful diplomatic missions, media attention, and accolades and awards than most professors achieve in a lifetime. He was also blessed with exotic good looks, charm, and charisma, and used them to his advantage. He enjoyed disarming his audiences by opening with: “Despite my Swedish appearance, I’m just a simple boy from the desert.” He later admitted that his success would sometimes go to his head – he knew he was a “big shot.” He came to indulge in the external trappings that came with his status. While never motivated by money, Said enjoyed certain luxuries. He became an avid collector of various objects: old books and coins, swords, exceptional pieces of African and Arabic art, and even cigars. He also invested a great deal in his wardrobe and gained a reputation as the best dressed professor on campus. On the surface Abdul Aziz had achieved everything he could have dreamed of and more, but he began to feel internally unfulfilled. Once when a close friend complimented him on his looks, Aziz remarked, “This is all that is left of me – just style, no substance.” He began to look outside himself for greater meaning, reading books on various religious and spiritual traditions and on personal growth.

Just as he began this search for meaning, an unexpected turn of events dramatically intensified it. Soon after he turned 40 in 1970, doctors discovered a mass in his lung. Based on x-ray images, the diagnosis was cancer. A lobe and a half of Said’s lung was removed in a serious operation that he barely survived. Fortunately, the initial diagnosis was incorrect; he did not have cancer. Ironically – given how the mere sight of sliced watermelon stayed with him for life as an example of American ingenuity – Said had aspirated a watermelon seed as a child and it had festered and become very infected.

This close brush with death was the final catalyst. Abdul Aziz decided he truly wanted to change his life and himself by embarking on a spiritual path of growth to seek a closer relationship with God, the Divine. This journey would be the lodestar that would guide his conduct and the direction of his life going forward.

When it came to religion and spirituality, Said was neither judgmental nor dogmatic. He believed all paths lead to the top of the same mountain. He likely chose Sufism as his “path” because fundamentally it is based on the concept of love – self-love, love of the Divine, love of others, and the unity of existence. During the second half of his life Said – paraphrasing the great Sufi philosopher Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi – repeated often: “Love is my religion and my faith.”

He was also attracted to Sufism’s emphasis on real world action. It stresses that through detachment from materialism and our egos, we can be in touch with the Divine essence that exists within each of us. By doing so, one can focus on actions that reflect the qualities associated with the Divine: compassion, unconditional love, and work to improve the human condition.

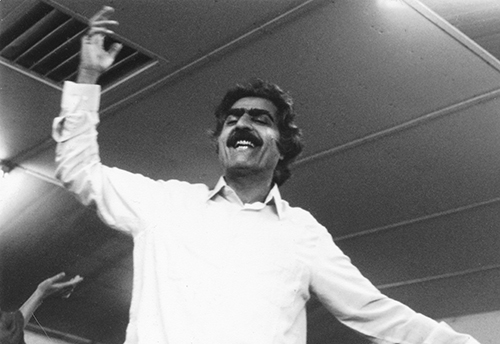

Professor Said demonstrating Sufi meditative dancing at an Omega Institute Conference in 1992.

Journey on a Path to Deeper Meaning

After recovering from his surgery, Aziz sought out a Sufi guide from near his village in Syria. He undertook intense spiritual work and practice, sometimes in person but more often via mail and phone for several years. His Sufi guide would send him instructions about prayer, meditation, fasting, and mandatory reading. His guide also stressed the need for detachment from material things – Said gave up collecting and by the late 1970s was proud of the fact that he only owned a single patched-up blazer. People who knew Said could see the change in him. Many noted that he exuded an extraordinary sense of inner peace and knowing: “he had a special light in his eyes.”

While adamantly opposed to any form of “guruism,” Abdul Aziz was willing to discuss Sufism and personal transformation with a wide range of seekers and members of other faiths who sought him out. By the late 1970s, he was speaking at well-known New Age venues, such as the Esalen Institute (California), The Omega Institute (New York), and The Findhorn Foundation (Scotland). His talks sometimes touched on international affairs, but he focused on spiritual transformation in a personal and global context.

During this period, Abdul Aziz befriended other scholars and thinkers interested in subjects like the role of the unconscious in human society. Said became very close to Dr. Willis Harman, a Stanford engineering professor and futurist, who wrote extensively on the need for a profound transformation in human consciousness to effectively navigate the increasing challenges of post-industrial societies. Said was also well acquainted with others in the New Age and Futurist movements, such as Ram Dass and Barbara Marx Hubbard.

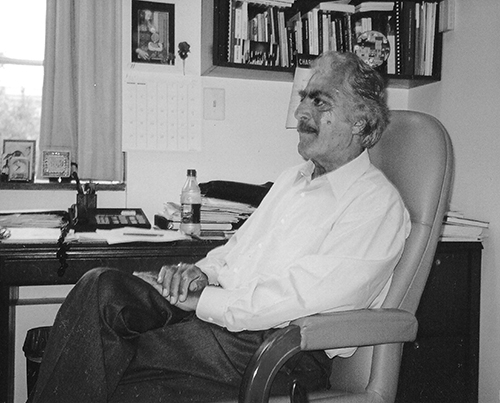

A meditative Said in his AU office in the mid-2000s.

Practice What You Preach: Scholarship from the Heart

Said’s commitment to the tenets of Sufism naturally extended to his academic and public service work, which became even more focused on issues such as human rights, global cooperation, nonviolent conflict resolution, and the role of spirituality in global politics. His steadfast commitment to these ideals helped him overcome opposition from skeptical colleagues and achieve his long-held dream of establishing AU’s International Peace and Conflict Resolution Program and his Center for Global Peace, dedicated to facilitating dialogue and the use of nonviolent tools to resolve disputes. As he taught and guided peace practitioners, he stressed the importance of internalizing the values associated with their own psychological and spiritual transformations before attempting to improve the lives of others.

Aziz’s personal journey helped shape his academic approach, including his legendary teaching style that valued students’ voices and treated them with kindness and respect. He also began to offer courses that discussed spirituality and its relationship to global cooperation and peace and explored these themes in papers and outside lectures. This was a risk – many scholars in the field viewed the introduction of spirituality into politics as flakey at best. However, as had been the case for most of his career, Professor Said was ahead of his time and laid the groundwork for another avenue of scholarly exploration. In 2014 the International Studies Association established the first subsection on religion, interfaith relations, and peace studies. In many ways, Said’s work became an external manifestation of his internal spiritual life and journey.

No One Else Like Him

American University’s longest serving professor teaching in 2015.

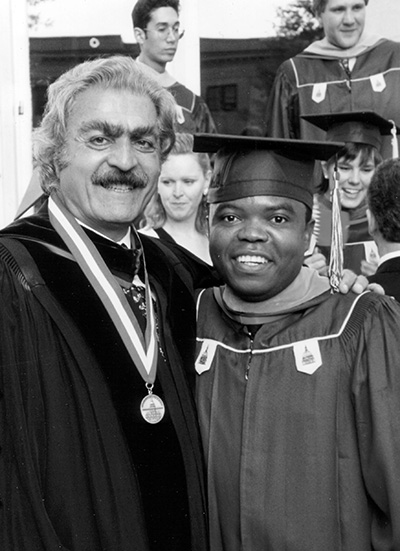

When Abdul Aziz Said joined AU’s faculty, he was the youngest tenured professor in the university’s history. He retired nearly 60 years later as its longest serving and oldest. He never slowed down over those decades, working full time advancing the cause and scholarship of peace, teaching his beloved students, and nurturing the university he called a second home. He was active even after he retired, offering advice and perspectives on a range of international issues – especially the tragic civil war in Syria.

It is difficult to sum up Professor Said’s legacy because he did and was so much. He pioneered new approaches to international relations. He countered the cold calculus of realpolitik with the warmth of humanity and empathy. He taught thousands of students to see the world differently. He helped shape AU into a world-class institution. He was a teacher and scholar, a philosopher of peace, a friend to ambassadors and janitors, and a spiritual voyager.

His impact on the world was tremendous. But his impact on people who were lucky enough to cross his path was especially profound. He always tried to see the good in everyone and treat every individual with dignity and respect. He deflected attention on himself by shining a bright light on others. Former students, colleagues, friends, and many others still comment on the effect his limitless faith in the essential goodness of humanity had on them: “changed the trajectory of my life,” “saved me when I was at my lowest,” “gave me meaning and a sense of purpose,” “strengthened my faith,” “no one had a greater influence on my life,” “there really is no one else like him.”

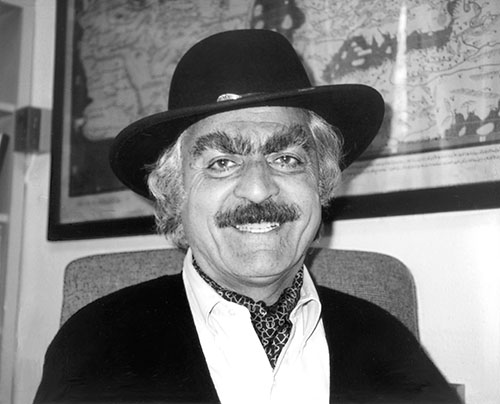

Abdul Aziz with the only hat he wore. This cowboy hat, a gift from his wife, was symbolic to Aziz because he would often refer to his youth in Syria as being like “living in the wild, wild west” – one reason he was a great fan of American cowboy movies.

The Sufi poet Rumi wrote, “Yesterday I was clever, so I wanted to change the world. Today I am wise, so I am changing myself.”

Over the course of his long and meaningful life, Abdul Aziz Said – the child of war and man of peace – managed to be both clever and wise.

PROFESSOR ABDUL AZIZ SAID

PROFESSOR ABDUL AZIZ SAID